Food delivery is on the rise – but is it always safe?

By Linda Everis - 18 December 2020

COVID-19 has obviously been devastating for almost every aspect of the food industry, but perhaps a calling for food delivery. Even at the earlier stages of the pandemic, the total number of food delivery users rose to 22.5 million – a 9.8% increase compared to the same period in 2019, according to Statista.

There’s no doubt that we’ve seen an explosion in food delivery this year. You may have even found yourself mixing up the flavours of your week with a meal-kit company. Supermarkets have been jumping on the bandwagon too and expanded their delivery offering by partnering with takeaway courier groups to meet the surge in demand. This expansion is essential, especially for vulnerable customers who are most at risk if they contract COVID-19. However, with this rapid expansion come concerns over food safety.

Food delivery: a key ‘takeaway’ from COVID-19

It doesn’t take a scientist to realise that when a country locks down and restaurants close, more people may seek food that can be brought to them. What does require a scientist, however, is a study to determine whether chilled food that’s being delivered remains chilled. To be precise, 8°C is the maximum temperature at which chilled products sold in the UK can legally be stored. Exceeding this temperature could make foods unsafe and susceptible to spoilage impairing the quality of the delivered foods. External environmental factors also need to be considered. For example, the UK summer saw temperatures soar above 30°C, meaning this legal maximum leaves little room for error for non-chilled food delivery.

Chilled courier is technically the safest way to deliver foods that need to be kept chilled but transporting products in this way can get expensive – hence why non-chilled courier or delivery via the postal service is more popular. However, foods delivered with these services are potentially vulnerable to fluctuations in temperature that occur throughout the day and night. This prompts the question: can these forms of non-chilled delivery prevent food and drink products from exceeding 8°C? To find out, our team of microbiologists promptly conducted a comprehensive study.

Research into temperature abuse during postal delivery

The method was simple. Chilled and frozen ready meals were packed into a cardboard box with ice packs and bubble wrap and then stored at various temperatures, mimicking those encountered during non-chilled delivery.

From braised steak to vegetable bake, each box of ready meals was subjected to one of three different temperature regimes that replicated worse-case food delivery processes:

- Regime one: 53.5 hours at 20°C or above

- Regime two: 15 hours at 5°C with a further 24 hours at 20°C or above, or

- Regime three: 10 hours at 5-8°C followed by 59.5 hours above 20°C

What did we find? In short, if products are delivered by non-chilled courier and are subjected to prolonged temperature abuse (meaning they’re stored above 8°C) then they may not remain chilled. This may seem like a no brainer, but the data allowed us to visualise how foods behave when exposed to these conditions. Why is this important? Because it can provide us with the insights we need to understand how, for example, to pack foods to increase their chance of staying chilled for longer.

What the research revealed

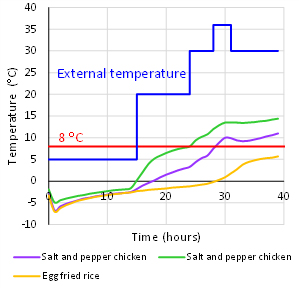

We learnt that the rate at which a product reaches 8°C can depend heavily on the type of product it is and (sometimes) its placement within a box. A perfect example of this can be seen in Figure 1 that represents data from a box stored under the conditions of regime two. Some variation is seen between the three products (the green, purple and yellow line) despite all of them being stored at the bottom of the cardboard box. As a result of this variation, two of the products exceeded the UK legal maximum storage temperature, indicated by a red line in the figure.

Surprisingly, ready meals kept at different levels within the same box sometimes behaved quite differently. For the box mentioned in the example above, a ready meal at the top of the box also remained below 8°C throughout, but several of the meals in the centre exceeded this maximum legal temperature (data not shown).

As expected, the external temperature played a pivotal role in increasing the temperature of the ready meals. What we’ve seen for the first time, however, is just how rapidly they warmed up. Looking at the worst-case example in Figure 1, the salt and pepper chicken (the one represented as a green line) climbed 8°C from 0°C during nine hours at a 20°C external temperature, putting it directly on the cusp of exceeding the UK legal maximum storage temperature.

When it comes to transit time, how long should food and drink be out for delivery? Our data has shown that if these worst-case scenarios are expected then these products should be delivered within 24 hours to ensure they stay chilled, even when ice packs are included.

What can the food industry learn from this?

The research highlights the three main questions that food businesses must ask themselves before sending their products out for delivery: how long will they take to reach the consumer? What time of day will it be? And are they packaged sufficiently to remain chilled?

Careful consideration should be given to the amount of insulation, packaging material, ice packs used and even the placement of products. This is particularly important when it comes to mixing products of different temperatures as we found that some chilled ready meals began to freeze if placed between two frozen ones.

With this in mind, a manufacturer may be tempted to pack products tactically to increase the likelihood of them maintaining temperature, especially if a long delivery time is expected. However, there’s no guarantee they would remain under 8°C during non-chilled transport. Providing product quality would not be affected, another approach could be to send chilled products out frozen, potentially helping maintain temperature control.

Overall, as mentioned earlier, the rate at which a product reaches 8°C can depend heavily on the product and its placement in a box, and it’s for this reason that we suggest food businesses undertake studies like this one before embarking on this type of delivery service. This is a service that our team of highly experienced microbiologists at Campden BRI can perform. We can monitor the temperature of products prepared for delivery and use the data to predict the potential for growth of both pathogens and spoilage organisms. Get in touch to find out more – we’d love to hear from you.

Linda Everis

+44(0)1386 842063

linda.everis@campdenbri.co.uk

About Linda Everis

Linda has a wealth of knowledge, experience and expertise from her time in Microbiological Analytical Services and Microbiology Safety and Spoilage. She joined Campden BRI in 1995 as a Senior Technician in the Microbiological Analytical Services group having graduated from the University of Wales Aberystwyth with a BSc in Biology.

Alongside the expert support that Linda provides to our members and clients, Linda conducts project work and research, and has been author and co-author of articles and papers for a variety of microbiological publications and Campden BRI reports.

Linda also lectures on shelf-life, challenge testing and predictive microbiology for our many training courses and seminars.